Terry Hawkins: ‘I’ll keep going until I can’t'

Film inspires young man’s dream, and a business that’s still delivering sweet music nearly a half century later.

Sometimes art really does imitate life. Or maybe it’s the other way around.

Terry Hawkins would know. He first lifted a trumpet to his lips not long after he saw the film, “A Young Man with a Horn.” The year was 1950 and he was in seventh grade at the time, still slogging through piano lessons his parents pushed him to endure.

“I started playing the piano when I was 5. I took lessons from a neighborhood teacher and I didn’t like it very much,” Hawkins remembered.

Though he found those sessions boring and tedious, Bess and Ches Hawkins were thrilled that their son was letting his fingers do the talking in a way they could never afford as children.

“They both loved music but grew up during the Great Depression. They never had a chance to do what I was doing. They wanted to give me an opportunity.”

Then, on a frigid February day, Hawkins pulled out 35 cents from his pocket, a handful of popcorn from a bag, and fixed his eyes on the big screen as Kirk Douglas, Lauren Bacall and Doris Day captivated him with the story of musician Rick Martin and his obsession with jazz music. His life had changed even before the credits began to roll. So did the instrument he played.

“I loved that movie,” Hawkins said. “I fell in love with the soundtrack by Harry James. I wanted to become a jazz trumpeter after that. I started practicing for hours a day.”

There’s a memorable exchange in the film where Martin’s teacher, Art Hazzard, has come to inform his student that he is heading out on the road with his band. And he might not be coming back.

“I want to go, too,” Martin tells him. “I want to be a trumpet man and get me a job with a good band, like you.”

Hazzard warned him of the pitfalls and pleaded with him to choose a different career path.

Like Rick Martin in the film, Terry Hawkins chose to listen to his heart. And that heart, twice repaired by multiple bypasses, continues to beat in 4/4 time.

Hazzard: “You can’t (go on the road with me).”

Martin: “Why not?”

Hazzard: “Even if you could, you shouldn’t. You’ve got to think about what you’re going to do.”

Though Terry Hawkins has seen the bright lights, the big city and all the trappings of a musician, he’s never really cared for all that jazz. He just wanted to spread his love of music to anyone who would listen. Or learn from him.

So on Dec. 7, 1968, he and his wife, the former Ginny Croyle, opened Hawkins Music Store on 3rd Street in New Brighton. It was his 30th birthday, but it also could have been described as his Independence Day, too.

Hawkins had been working for a decade at the American Bridge Co. but wasn’t fulfilled with his accounting job. He was looking for a way to pursue his passion full time.

“I didn’t like working for other people. I really wanted to do something for myself. I figured the only thing I really knew and loved was music.”

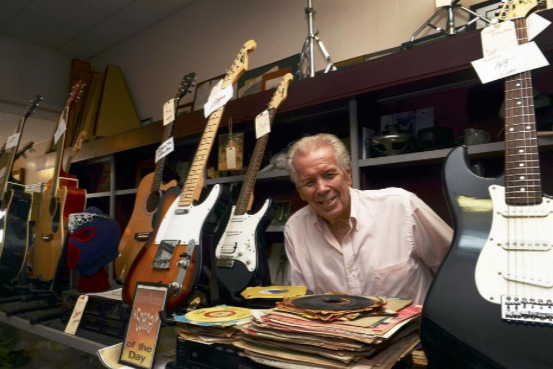

So he and his wife began selling new, used and vintage instruments. They ranged from guitars to drums to pretty much everything in-between. Musicians would recognize the brands immediately: Baldwin, Fender, Ludwig and Gibson. Hawkins was never happier.

“We did really good for a long time. We actually operated in this entire block,” he explained, pointing slowly from 8th Street north to 9th Street south.

Terry and Ginny had three buildings filled with instruments and still struggled to keep up with demand.

“There was a lot of foot traffic downtown at the time,” he recalled. “Lots of people were coming in and out of the store. Lots of kids were playing instruments. It was always a thrill to put a fine instrument in their hands.”

He remembered patiently helping children make the right purchase as they visited with their parents. Hawkins knew how important a good fit was. After all, he was just a kid himself when he began to earn a sterling reputation for his musical prowess.

While a sophomore at Rochester High, Hawkins was selected to play with members of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra. That same year, he began to play for pay with a few music combos in the area.

“I had a great time. And we played a lot. I had to quit the high school band my senior year because we were always booked.”

In the 1980s, he formed the Terry Hawkins Jazz Trio and began performing in some of the most popular spots in western Pennsylvania: the Top of the Triangle, Antonini’s on the South Side, Bravo Franco, and a standing gig at Alex Sebastian’s Wooden Angel in Beaver for the past two decades.

Even at age 78, Hawkins boasted that he still hasn’t missed a Friday night in 22 years. “I’ve never skipped because I was sick or anything like that, although I’ve been sick on occasion.”

His commitment, he insisted, is not inspired by a paycheck. “In all honesty, I would play for nothing,” he confessed.

He smiled and rubbed his chin. “But don’t tell anyone that. I don’t want Alex to get any ideas.”

Hazzard: “You think playing is all there is to it?”

Martin: “You taught me to play a pretty good trumpet, didn’t you?”

Hazzard: “You play a fine trumpet, but …”

Stay in business for nearly 50 years and, sure enough, you pick up a nickname. “I was the Godfather of the Nuts,” Hawkins said, chuckling. And he’s got the pictures to prove it. Caricatures, to be exact.

Several pencil drawings line the back wall of his shop. They were created by Becky Pyle, a friend of his. There’s one of Chuck Haffey. There’s another of Jimmy Hart. Bobby Eakles and Tom Vok are there, too.

“They were all well-known characters in New Brighton,” Hawkins explained. “They always stopped in to shoot the breeze. They were great guys.”

Hawkins must’ve had the power of attraction, because those local legends weren’t the only familiar faces to set foot inside the store. And Hawkins has the pictures to prove that, too.

Glass cases lining both side walls serve as time capsules to a bygone era. Those memories remain fresh today through framed and signed photos of such music luminaries as Gene Krupa, Leon Redbone, B.E. Taylor, Harold Betters, and Pittsburgh icon Joe Negri.

Hawkins laughed when recalling a visit by Redbone, who had performed in Pittsburgh the night before. (For those of you unfamiliar with his music, he played Leon the Snowman in the movie “Elf.”)

“We had been talking and I said, ‘boy, you sure do a good imitation of Leon Redbone.’ Then he said, ‘I am Leon Redbone.’ ”

The singer bought a slide trumpet — “a very unusual piece,” according to Hawkins — with his credit card. “I looked at the card and, sure enough, it said ‘Leon Redbone.’ It was really him.”

As the 1980s gave way to the ’90s, Hawkins experienced two major changes that set him on a different course — personally and professionally. Heart trouble forced him to undergo two bypass operations within a span of seven years, so he no longer had the stamina to play the trumpet.

Enter Dale “Doc” Mancell, a trombonist, arranger and pianist from Rochester. He began to teach Hawkins the theory and harmony of the piano.

“Doc had played with a lot of big-name bands and was really talented. He really helped me to fall in love with the piano.”

At the same time, traffic inside the store had been on a steady decline, even though Hawkins had spent thousands of his own money to update the facade on his buildings. A framed picture displaying his shop’s sparkling new look still hangs on the wall near the back counter.

“The council used to call us the gem of the downtown.”

So Hawkins got the idea to expand his reach. And in a pretty big way.

“We started doing a lot more business on eBay,” he remembered. “We started selling vintage instruments all over the world. It was a good move for us.”

Not long after, Hawkins was devastated when his wife of 36 years died at age 63.

“I was playing with the Clark brothers in Coraopolis,” he said of that night. “She wasn’t feeling well and went to bed early.”

When Hawkins got up the next morning, he had discovered his wife had died of an aneurysm.

“She was a smoker. She smoked for years and I tried to get her to stop …”

His voice trailed off as he fiddled with some papers on his desk.

Ginny left her husband behind with no children, but a brood nonetheless.

“We never had kids but we had 11 cats when she died.”

One of them, named Satin, continued to live with Hawkins until she died two years ago at age 21.

“I never even liked cats. Now I’ve grown to love them.”

Hazzard: “What’s it worth? Look at me. What have I got after 20 years of it. A wife? Kids? Money in the bank? No.”

Martin: “Who cares? I don’t play for people. I play for myself.”

Hazzard: “Look, boy. You’ll stay up for a while. Then you’re going to fall.”

The once-bustling store is now empty some days. It’s a different time. A different world. Instead of picking up their keys and driving to the downtown, many adults are picking up their phones and ordering items online. Instead of picking up a clarinet or sax, many children are picking up their controllers to play video games.

“In the summer time, we used to have droves of kids coming in,” Hawkins lamented. “It’s nothing like that anymore.”

Dave Burhenn is a reading teacher at Todd Lane Elementary School in Monaca. He has known Hawkins since the early 1980s, when he began taking drum lessons at his store. He’s also played with him at a variety of gigs and still calls him a friend and mentor.

“Terry has always been the coolest guy I know,” Burhenn said. “I met him when I came to his music store to get drum lessons from a great jazz drummer who taught there, Jimmy Pasquale. Terry is the blueprint for a ‘jazz guy.’

You can tell from the slang he uses to his obvious love for the music he built his business around.”

After making sweet music together through the years, Burhenn and Hawkins are now talking about collaborating on a book.

“Roger Ryan of Pittsburgh was the best drummer I’ve played with,” said Hawkins, a 2003 inductee into the Beaver Valley Musicians Hall of Fame. “And Dave was second. Now that Roger is dead, Dave has moved to the top.”

Hawkins thought so highly of Burhenn’s work that he asked him to teach drums for him. Burhenn gave lessons from 2000 through 2013.

“Beaver County’s lost its interest in music, I think. We were seeing fewer and fewer kids coming in during my later years.”

On this warm, late summer day, a large ceiling fan circulated air through the shop. A small floor fan tried to keep up from the rear.

“We used to have air conditioning, but now it’s too expensive,” Hawkins explained. “Now we operate with fans.”

Inside the store’s front window is a set of bongo drums, flanked by a large yellow sign that reads: “Ask for sale prices on all items — we are dealing!”

A stack of old vinyl albums rests on the floor. On top is Bobby Vee’s “Golden Greats.” On a counter nearby is another stack of old 45’s, featuring The Four Seasons and other stylists from the 1960s. Brandon Camel had walked by the shop earlier in the day but was stopped in his tracks by what he heard through the open front door.

“Mr. Hawkins was on the piano and I had to stop and listen,” the 22-year-old New Brighton resident said. “I’ve never seen anyone play like that in person. It was phenomenal.”

Camel said he plays bass occasionally on the praise team at Champion Life Church in Chippewa Township. He asked Hawkins if he could take a look at one. Hawkins plugged a five-string bass into a nearby amplifier and handed the guitar to Camel.

“Have at it.”

Camel played some chords from his favorite band, Metallica. About 20 minutes later, another visitor walked through the front door. Hawkins struggled to get up from an old couch in a back room to greet him. He walked with a noticeable limp.

“My lower back and knees are shot,” he said. “Just old age.”

Nevertheless, he still does calisthenics each morning after waking up around 7:30 a.m. He arrives at the store around 9:30 a.m each day and opens for business at 10.

“Some days the phone doesn’t ring and no one comes in. But five minutes before closing I may make a couple hundred dollars on a sale. You just never know.”

Ralph Farrar dropped by and hoisted a black case onto the counter. Inside was an autoharp belonging to his mother, Marion Weister. At age 88 and now legally blind, she continues to find joy in playing the instrument.

“She taught herself,” said Farrar, a Beaver Falls native who now lives in Arizona. “She loves to strum away at home.”

Hawkins loved to play at home, too. That is, until he was forced to sell his 1958 Baldwin grand piano to keep the shop afloat.

“I really miss it. It’s sad. I don’t have a piano at home anymore.”

Near the shop’s front door sits a Yamaha piano with two small signs resting above the keys: One reads “not for sale” and the other, “do not play.” Those messages are meant for everyone except Hawkins. He slowly made his way toward the front of the store and took a seat.

Moments later, he eased into the gorgeous strains of “Misty” from the film “Play Misty for Me.” He followed with “Tenderly,” a song made famous in the 1953 movie “Torch Song.” He looked up and smiled.

“This is the same kind of piano I play at the Wooden Angel. You know, I’ve been using what they pay me and my tips to keep this place open.”

He extended a hand to bid a visitor goodbye.

“I’d love to see the business turn around. We’re approaching 50 years now. I’ll be 80 and I’d really like to be around for that.”

The young man with a horn is now a wise old man on the piano. And he wouldn’t change a thing.

“I’m never going to retire,” Hawkins said quietly. “I’ll either die in this store or behind a piano. It’s what I love to do. And I’ll keep doing it until I can’t.”

Maybe sometimes art really does imitate life.

Or maybe, it’s simply a vivid reminder of what truly makes our hearts sing.

(This article appeared in the Beaver County Times on September 21, 2016.)